It’s been an action packed summer for the Stina project. I’ve been holding off on writing a blog about it, as I wanted to get to a point where we could take a breath and reflect on all that has happened, what it all means and where we are now in the project. There have been high points and low points and a lot learned. This will be a longer piece than usual, as there is so much to cover and I’ll break it up into roughly chronological sections.

Cannes Film Festival

Site of our first meeting – “English Pavilion” behind the “Palais des Festivals” Screening Area.

When we first got accepted to the “Court Metrage” at the “Festival de Cannes” we were very excited. This is the biggest art house film festival in the world, and many of my favorite films, and ones that have been a big influence on our production such as “The Conversation”, “Paris Texas”,”Mulholland Drive”, “Picnic at Hanging Rock” have won big prizes here. We are very proud of our short film “Uncle Griot”, which although not able to compete against fully formed 15 minute short films, (ours is only 5 minutes long, and assembled from a single scene in the feature) works well as an atmospheric slice of our feature production, with enough ideas and emotion to at the very least leave the audience with a lot of questions, if not all of the answers. So when it appeared in the official Cannes catalogue alongside works from well known directors it was a real buzz. Our intention was always to use it as a tool to open doors to help the feature development and hopefully interest a producer enough to come onboard and help with our next stage of funding. It became clear though, after collating assorted and often contradictory views on the festival, that acceptance to “Court Metrage”, although framed as an opportunity only open to those who have a project that is quantifiably “art house”, it is in fact simply a pay-to-attend market place, where thousands of short film makers try and forge a career or, as in our case, battle to get funding for their feature development. It isn’t, as it initially appeared, any kind of stamp of approval on the quality of your film. We were to be an incredibly small fish in a very large ocean of highly seasoned, and extremely busy producers, sales agents and distributors, and lots of other very talented filmmakers, (who are all trying to compete for the same limited funding and opportunities.) As a result of realizing this we did as much research as we could before we left, to try and make the best use of our time. One thing that became clear was that there is no point going to Cannes unless you do the leg work to arrange meetings before you go, as most producers have filled their schedules before their planes even touch down. This was a very new world to me. My experience in the film industry has always been on the filmmaking side and never on the film producing or funding side, so it was an intimidating first step.

“Uncle Griot” Cannes Catalog Entry.

The first stage was to “reach out” (a phrase I used a lot for the next 3 months), to as many people as I could to help us. A thing we learnt quickly was the importance of knowing exactly what you are asking for and what, specifically, you are offering. Film producers, sales agents and distributors deal with hundreds of cold callers and have neither the time nor the inclination to humor unprepared newcomers. So to this end I embarked on as thorough a research and costing of our entire feature production as I could. Amongst my most useful meetings was a chat with the head of feature animation development at Double Negative, who as well as generously giving me a lot of his time, gave me a lot of good advice on the language a producer expects to hear in regard to animated film costing (The currency is seconds per week; 3 for feature quality, 6 for TV, and so on). I also approached the company REALTIMEUK to help us cost a version of the production done with the UNREAL game engine (more on this later) as using a game engine had the potential to bring the costs down to a manageable level.

So, what is a manageable level? This is the million dollar question (probably more). Up until this point our production had existed in a safe university bubble. We had been developing at our our own very slow, but comfortable pace, but the reality of finishing a production as complex as this without it taking 50 years, is that at some point you need a big injection of cash. There is no real way around that, down simply to the volume of work required to service a 2 hour film. My research on this led me to a number of areas that need to be fleshed out. The first area was the basic marketing one. In selling a film to a producer, distributor or sales agent, by far the most important thing is to know is where the market for the film is, and whether it can realistically provide enough budget for your production. The second concern is: why should the producer trust your skills? And why should they believe your specific film will make the investors any more return than any other projects on their desk? These two areas can be summed up in two words: “Reputation” and “Return”. Almost every producer we spoke to before and during Cannes, at some point, uttered these two words.

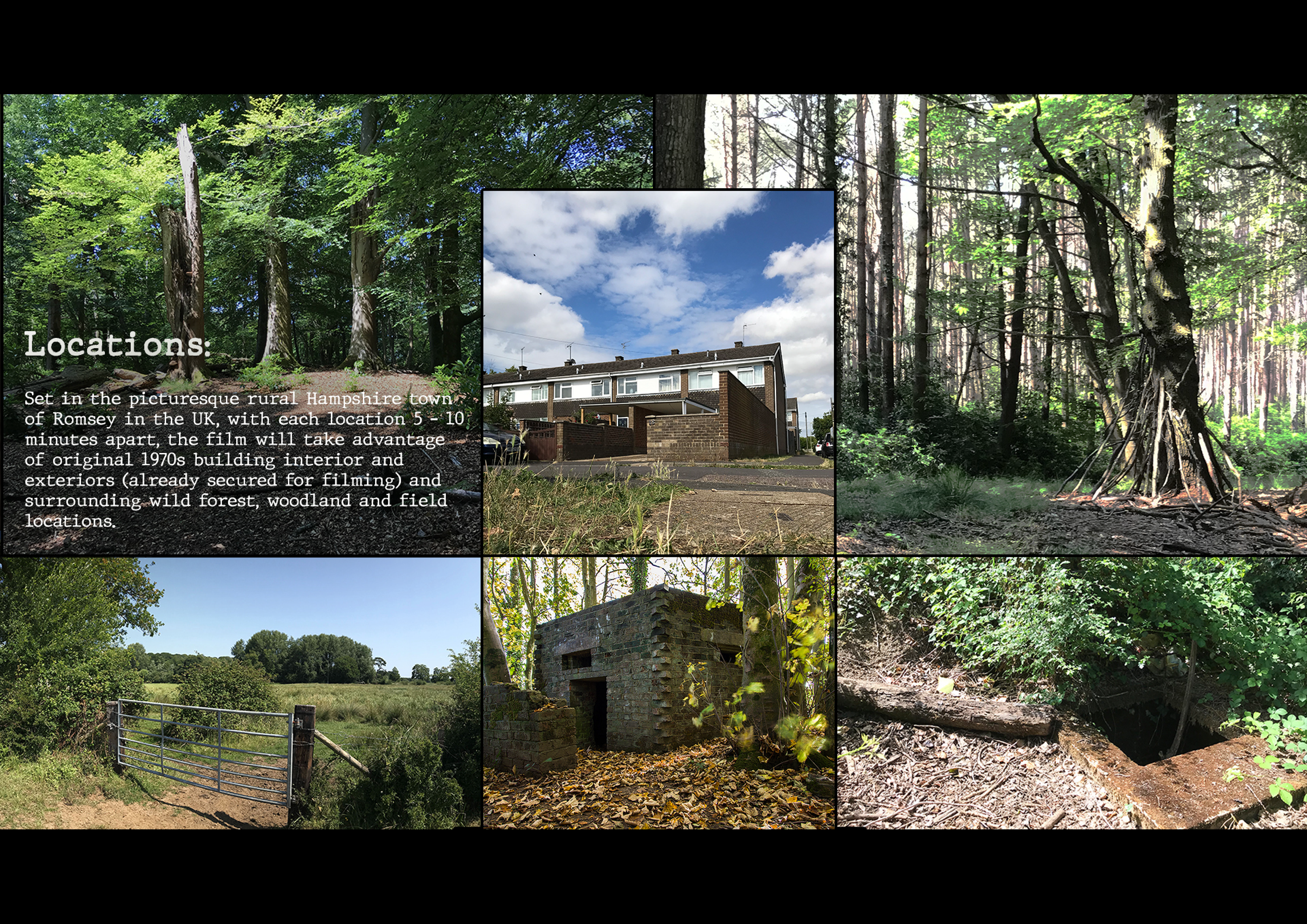

To tackle the cost of our production we looked at recent similar film projects. There is a precedent for cost-saving productions using the Unreal game engine. One such film is the recent “Allahyar and the Legend of Markhor “. The production company have been very coy about their actual production costs for this film, but it is well known that it was substantially cheaper than similar traditionally made CGI feature projects. We initially worked with UNREALUK to help us cost this, but unfortunately they couldn’t provide us with a quote in time as they were in the middle of multiple big productions, so we looked for other assorted reference sources and came up with an initial budget for the whole feature. This figure assumed we would be using Unreal and was based on a breakdown of animation, modelling, rigging, VFX, tools, production, foley, mixing and grading guided by our assemble of the film (a 110 minute long cut constructed from on-set reference footage, storyboards and concept art) It came to $2.5 million. This would pay for a small professional animation studio, staffed with junior- to mid-level artists and a few seniors working for two years. It would also allow us to formalise the student contribution, by running year-long paid placements as part of the degree program. This budget sits well in the indie horror market, which is a realistic genre to pitch to, given our content . “The Company of Wolves”, a film that shares some thematic similarities with our film was also marketed as a horror film, even though it’s predominantly an Art House experiment. So this approach can work and stay true to both the marketplace and the work.

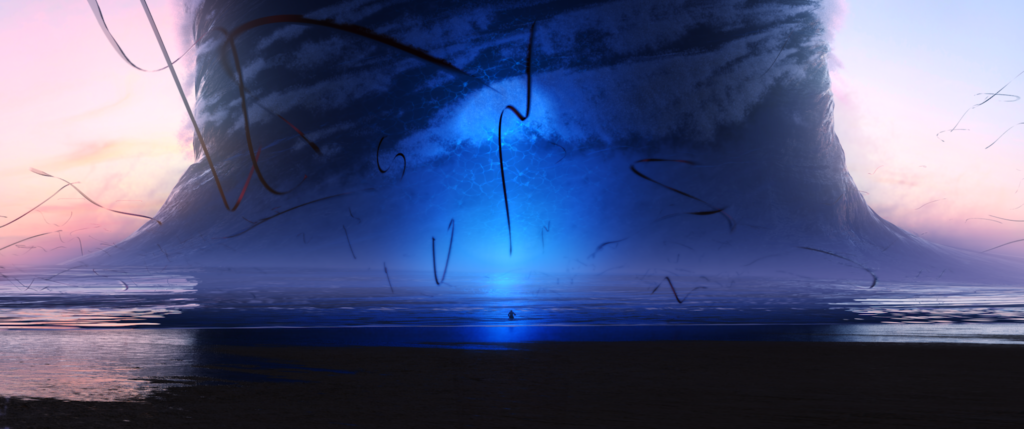

Our poster and part of our “Pitch Deck” for the “Stina & the Wolf” horror pitch.

The indie horror market in particular can accommodate films budgeted between $500K and $3 million, which can generate at least $10 million in Producer’s Net Profit with Income Streams: 28% from theatrical, 60% from home video and 11% from TV and other ancillary income. This could also provide an indication of our distribution approach. Lessons from research into these lower budget films also told us we should look for “good actors, not big stars, and do the same with all of the technical crew on a film”. This, fortunately, is a fairly accurate description of our project: great performances and visuals,but absolutely no-one famous involved!

So, with all this information, a “pitch deck” on our Ipad and a single meeting I’d managed to setup with a producer I’d managed to wrangle from existing contacts I have in the film industry from my VFX days (after countless fruitless other attempts by email and phone to assorted production companies) Alex and I headed off to Cannes, feeling a bit like 2 Mr Benns having taken the producers outfit off the rack, slipped through the shop doorway and disappeared into a new and very surreal world.

Paul and Alex pretend to be in the film industry.

On arriving at Cannes our meeting was immediately postponed to the following day due to what sounded like a stressed and overworked producer juggling a production disaster unfolding in real-time on her main Cannes film project. We had definitely arrived at the chaos-center of the film industry. Her film was to be a big highlight of the festival, and last minute hitches in its world wide release were apparently causing release-busting problems. The next day we got our meeting, albeit with a few breaks for emergency fire-fighting calls to various parts of the globe. It was useful, and she was very direct. She made it clear the kind of film we were trying to fund had no chance of US funding, no chance of a traditional animation feature blockbuster funding (no stars/No award winning director/writer) but sounded like a good potential fit for the “Asian market”. For the following days we attended as many assorted networking events as we could and learned about the feature production world, and how its various parts fit together (or don’t!). Again and again we were told our film fitted into the “Asian market”. After a week of this we came away somewhat shell shocked. The experience of coming in as newcomers to a such a complex and established market place was a little overwhelming, and for the most part we were out of our comfort zone, and out of our depth. Also the festival as a whole (some great films aside) felt somewhat flat and even a little paranoid, as it was trying to reinvent itself and re-commodify its “glamour” in the light of the Harvey Weinstein affair (one taxi driver told us that it was the Weinstein entourage that pretty much made the festival every year, and as a result many of the usual crowds of American tourists were absent) The festival is trying to find its way in response to the “#meto” movement. And rightly so.

Queuing starts outside the “Palais des Festivals”

All in all the film industry circus in Cannes is not a place for the faint hearted, or the inexperienced. It’s a place where established film producers and distributors negotiate deals with established award winning film makers. (A lot of whom do all of their deals and leave the week before Court Metrage even begins, as they aren’t interested in sifting through the hundreds of short film makers) We didn’t find a producer in the end. This was a baptism of fire, but also an extremely valuable learning experience and one that will definitely inform the rest of our production. We are now equipt to talk to producers in a language they understand, and are now actively investigating the much lauded “Asian market” to see if this is indeed where our future lies.

Siggraph 2018, Vancouver

Alex chats to another speaker as the room starts to fill up ahead of our talk. (It filled up, honest!)

As well as dipping its toe into the hectic world of film funding, the project has also been delivering on its academic and research objectives. This was our third trip to Siggraph, but this time we actually had a paper to present. We were very surprised and pleased to have our submission accepted in the “Arts Paper” section. (The competition is pretty fierce at Siggraph, as its the leading international conference for Computer Graphics, Animation and Visual Effects) . The paper dealt with some of our funding challenges, as well as getting into the thematic and narrative ideas at the heart of the film. On a personal level, it was great to get back to some of the ideas in the actual story, as opposed to the funding and contractual aspects we’d been obsessing about all summer. (Definitely not my natural skill-set!)

Our paper as it appeared in the M.I.T. LEONARDO journal, and 2 nervous presenters.

The conference was excellent, and we were very much back in our comfort zone. (Alex was flogging another project here also: a VR theatre experience called “Fatherland” and there was a lot of exciting VR technology around) Our paper seemed to be well received and it was great to feel part of the arts community there. The talk was well organised and we were made to feel very welcome. The conference stalls, exhibitions and presentations gave us loads to think about regarding game engine usage for animated feature development. It made us realise the real-time aspect of using a game engine in “Virtual production” would definitely allow us to use much more reactive and traditional filmmaking techniques, much more akin to being on-set, as well as helping to bring the production costs down. There was also a lot of AI and deep learning software on show; it was clear how fast the technology is progressing in animation and rendering tech. Hopefully the near future is going to bring a lot more speed and automation to a lot of tasks which are, at present, very expensive and very time consuming.

Rewrites & Table Reads

One of the main goals of pitching to a producer is to get them to read your script. (or get one of their script-readers to read your script) The script is the blueprint for a film, without it, traditionally, there is no film. We are in a weird position in our production, in that we have effectively completed our “principal photography” on our mocap stage. We also have a rough cut of all of this with music and some foley and effects. As it stands however this cut still requires a lot of imagination to make sense of, as some parts are storyboarded better than others and some parts give limited context to the action, as they’re edited from raw, fixed, reference camera footage from the shoot. As a film, it only works in the context of having read the script. It was a tricky decision whether to use the drama cut or the script to pitch our project, as they both have their own merits, but in the end we went for the script, as certainly in the world of Cannes, this is the expected format.

The Pipe Catcher spins a tale to Stina & her friends at the Night Fair.. (Played by the amazing Martin Daniels; audio from our 2 hour “Drama Cut” )

Our first job was to rewrite the script to add in new sections. An old cliche in filmmaking is that you make a film 3 times: once when you write it, once when you direct it and once when you edit it. We had made all sorts of script changes during the shoot and again in editing the drama cut. The first task was to get all of these changes back into the screenplay, so it more closely represented our vision for the film.

The second job was a more difficult one. Our film, by its very nature is challenging. Its influences: films like “Mulholland Drive” , “Picnic at Hanging Rock”. “Don’t Look Now” , “The Company of Wolves” are not traditionally commercial products, or certainly not in today’s film market place, and they rely as much on visual atmosphere and symbolism as they do on the more traditional elements of dialogue, exposition and traditional narrative form. I shall use another blog post to go into our approaches regarding narrative and symbolism, but it was always a worry that we needed to find a willing producer to give us feedback on where our film sat in the gradient between commercial and art house

We want our film to work as a horror film, but also as much, much more. I wanted to get some external views on our screenplay, as we needed a dry-run of what an average producer might think on a first read-through. As I discovered fairly quickly, nobody is going to read your screenplay as a favour. As with all things in the film industry, you need to pay for it. It wasn’t cheap, but I got a “Hollywood” read-though and paid the extra for written feedback. The feedback made it very clear this film was never going to be a mainstream box office smash. The reader didn’t understand a lot of what we were doing and our task (as difficult as this was) was to try and sift through all of his feedback and decode what was, and what wasn’t relevant to what we want to do. (Feedback should always be approached with honest reflection, but also caution. It can totally destroy a project as well as save it if it’s just taken verbatim. To quote a screenwriting lecture I once attended: “Opinions are like arsehols, everyones got one”) What was very useful was that it highlighted a few issues of clarity in our ideas and made it clear certain areas need strengthening and others needed to be readjusted to help the balance between narrative hand-holding and audience heavy-lifting. This is always a challenge for “art house” work, as at one end you have Hollywood characters screaming the plot at you every time they open their mouths, and at the other end you can end up with a vague pretentious mess of arty stuff that’s incomprehensible to everyone except the director. Our job, as i see it, is to try and give the target audience enough ingredients to make their own soup, but with enough guidance from our recipe that they could come up with their own tasty concoctions, and maybe even some that would never have occurred to us. (In my opinion this is what David Lynch miraculously achieved in “Mulholland Drive”, although this film requires a number a watchings to fully savour. But that’s another debate) This approach also reflects some of the thematic elements we are trying to explore, such as fugue states, symbolism as a creative act of perception by the protagonist and other pretentious sounding but well intentioned ideas I shall dive into in a future blog. That’s enough with the bad food metaphors I think.

So, the result was I did a rewrite and inevitably the process of doing so led me into discovering new ideas and new ways of crafting the story and the characters experiences that I hadn’t originally planned. It also took the screenplay from 65 pages to 110 pages (110 pages is the mean average of pages needed to get a film made, according to various sources. This assumes a minute a page, not an entirely reliable assumption for our film, as the original 65 page screenplay drama cut was 110 minutes long)

Table read of the new screenplay – Clockwise left to right: Paul, Becky, Freya, Fiona, Ken, Sheila, Evie, Adrian.

The result of this rewrite means we now need to shoot some additional mocap, as there are now additional scenes and some dialogue changes (although about 2/3 of the film remains unchanged) To this end I decided a table read would be useful, as hearing a screenplay acted out is an essential part of crafting a finished version. Words that sound great on the page don’t always work with the rhythm of a particular actor or actress, and there is no easier way to see if you’ve overwritten a scene, or have put a joke in that falls totally flat, than hearing it read out-loud in front of you. We had just enough time to organise our original Stina actress: Becky Waldron and our original Mahdid actress: Evie Payne, to take part, before we left for Vancouver. (Thanks also to Freya Spencer, Adrian Samuels, Ken and Sheila Charisse for agreeing to read and delivering some fantastic performances!). Due to clashing events, we had to do the reading 2 hours after I got off the plane from Vancouver, so it was a slightly surreal jet-lagged experience for me, but it has proved extremely useful in giving us a sense of the film’s overall shape, as well as dialogue bits that need tweaking. Although we now have more work to complete, its very exciting to see the way the story and characters have been enriched by this process. Also, any excuse to spend time on the story and take a rest from fundraising is always fine with me.

3d Production Pipeline

As i’ve written about in previous posts, the majority of our production, up until this point (and for all of “Uncle Griot”) was completed using Autodesk Softimage. As Autodesk decided to end Softimage, we have had to start the process of rebuilding our entire asset library of rigs and tools again in a new software package we hope will stay with us for a bit longer. The software is called Autodesk Maya. Our plan is to get our custom software tools and rigs up to the same level of usability we had in Softimage, and then begin the process of Previz with the students. To replicate many of the tools in Maya, we are having to learn the object oriented programming languages of Python and PyQt, as a way to implement features we had previously built in Softimage’s node based programming system called ICE.

Griot’s facial animation system being rebuilt in Maya using Python and PyQt.

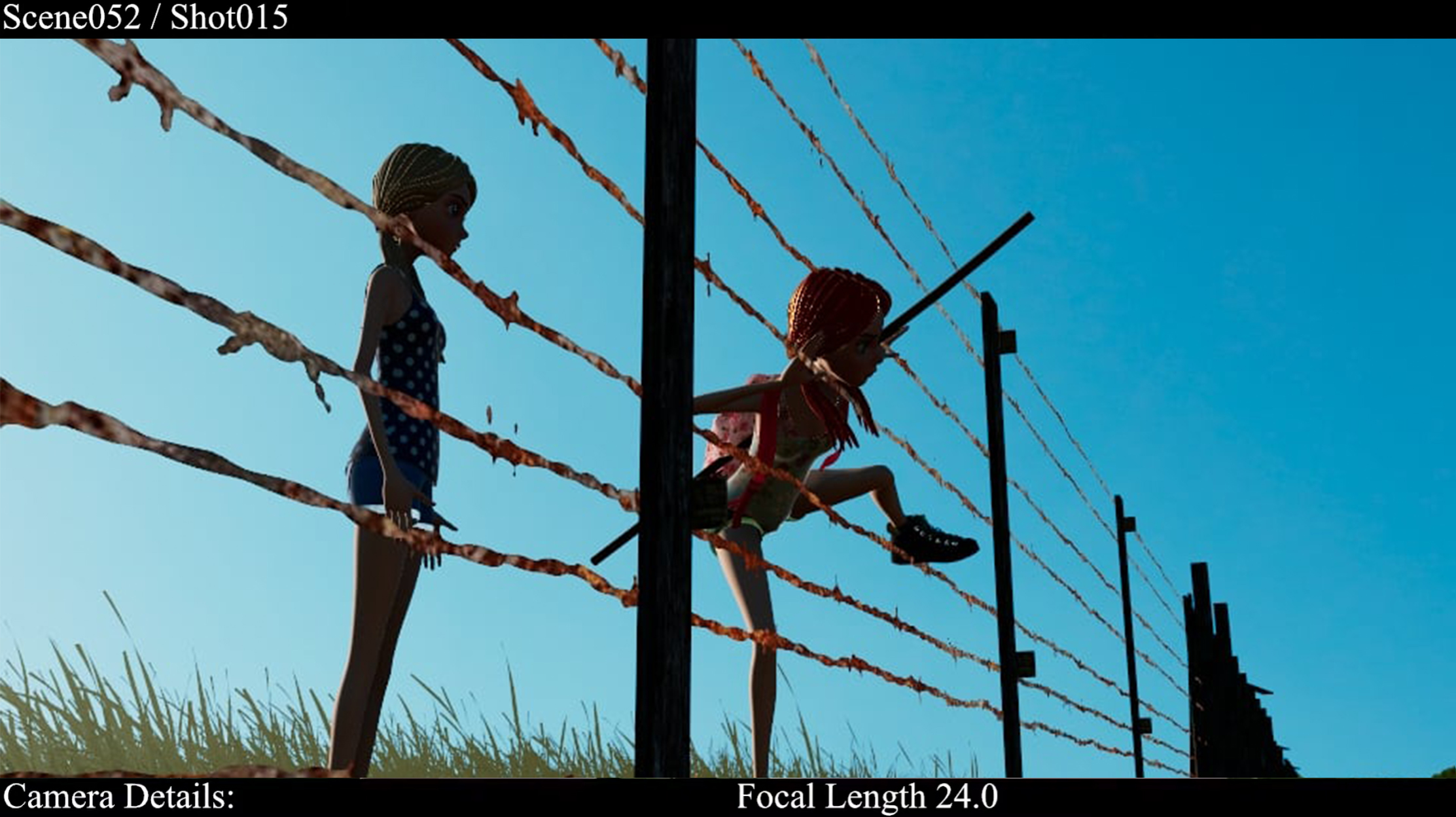

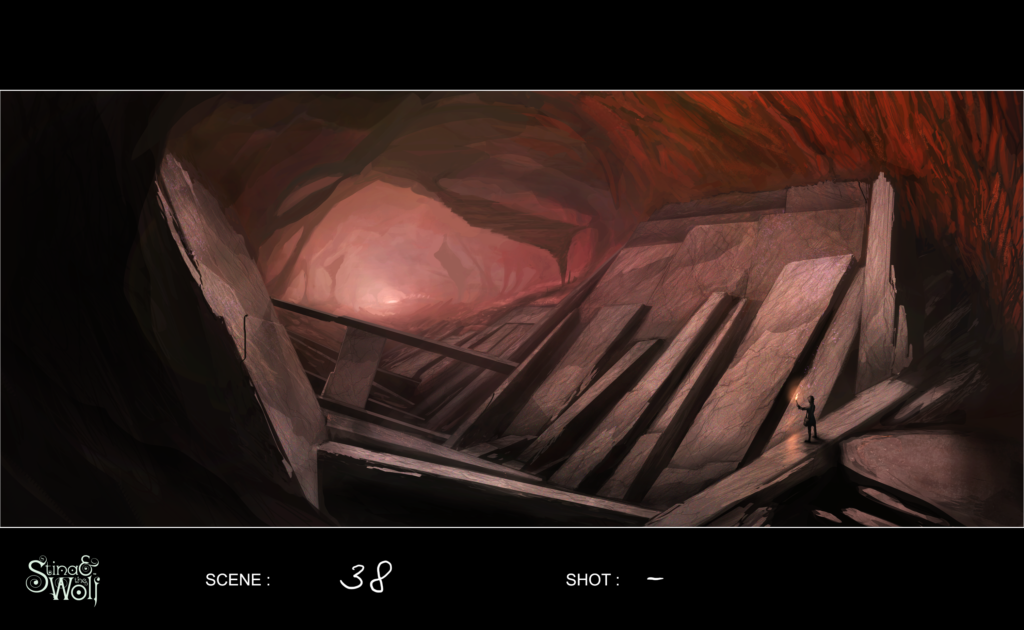

Previz involves doing a rough 3d block out of every shot of the whole film, similar to an animated storyboard. This allows us to time-out and plan what is required in each shot in detail. This is essential for costing the film, as well auditing what skills are needed for the higher resolution work (such as animation, modelling, texturing, fluid simulation, compositing etc). It’s also very useful as a guide for scoring the music, and starting work on the foley and dialogue mixes as well as the edit. The previz will be informed by our drama cut, which we are also revising at the moment to reflect our latest script additions. We are also planning to start work on experimenting with the UNREAL game engine as our primary renderer and investigate some of the virtual production technology we saw at Siggraph that works in the UNREAL environment. This will begin once our base assets are completed within Maya. We will also be continuing to work with FACEWARE as our primary facial capture tool.

Film Festival Success

I’ve been tweeting and posting regularly on facebook about our assorted film festival selections and awards for “Uncle Griot”, but I thought I’d end this blog by collating them all into one place. I am planning to release the film online at the end of the month, as it’s final festival submissions are almost complete. We’ve had a good amount of success on the festival circuit (We even managed to get selected for the Oscar accredited “Holly Shorts” festival in the Chinese Theater in LA!) and had some really great communication from festivals around the world (particularly from the “Florida Animation Festival”. There’s an interview I did with them in the previous blog post) It’s an expensive business, as each entry can cost up to $65, so you have to pick your festivals wisely, but we are very happy with the international coverage we finally achieved. (Although it did far better in the USA and Europe than it did the UK for some reason!)

- Official Selection for the Oscar-Qualifying “14th HollyShorts Film Festival” at the Chinese Theatre, Hollywood, CA.

- Award for 1st Place in 3d Animation at the “Florida Animation Festival”

- Award for Best Animation at the “Top Shorts Online Film Festival”

- Official Selection for the “Festival de Cine de Madrid”

- Official Selection for the “The International Animation Film Festival (IAFF) Golden Kuker- Sofia”

- Award for Best Editing at the “Top Shorts Online Film Festival”

- Official Selection for the “Toronto FEEDBACK Film Festival”

- Award for Best Score at the “Top Shorts Online Film Festival”

- Award of Excellence at the ”One Reeler Short Film Festival”

- Official Selection at the “Fantasy. SciFi, Film and Screenplay Festival” in Toronto.

- Official Selection at the “Philip K. Dick Film Festival” in LA / New York

- Award for Best Cinematography at the “Fantasy. SciFi, Film and Screenplay Festival” in Toronto.

In previous posts I had discussed making it as a live action feature; starting again, completely from scratch. This always stung, as there were so many great moments and performances from our original shoot that would be lost and need recapturing. At the time we just couldn’t work out a way to finance it, to get the huge budget you need to pull off an entirely motion captured film to the quality we wanted.

In previous posts I had discussed making it as a live action feature; starting again, completely from scratch. This always stung, as there were so many great moments and performances from our original shoot that would be lost and need recapturing. At the time we just couldn’t work out a way to finance it, to get the huge budget you need to pull off an entirely motion captured film to the quality we wanted.

Then 12 years passed by (Yep, it really was that long! This all kicked off back in 2010) and technology finally caught up.In the last few years facial animation technology has been massively democratised, as has access to amazing scanned models and real-time realistic lighting and cloud technology. This is best represented in the incredible new game engine UNREAL 5:

Then 12 years passed by (Yep, it really was that long! This all kicked off back in 2010) and technology finally caught up.In the last few years facial animation technology has been massively democratised, as has access to amazing scanned models and real-time realistic lighting and cloud technology. This is best represented in the incredible new game engine UNREAL 5: We are currently designing a pipeline for this new phase and planning to reinvigorate our old in-house studio FOAMdigital that ran out of Portsmouth University. It will once again give students a chance to get involved in a really exciting industry project that will take their skills to the next level and help them produce some really stunning work. (As seen in our short film “Uncle Griot” & our assorted trailers and teasers.)It’s early days, but we shall be posting more details, examples and deep-dives as we progress, and with the addition of the University’s amazing new £7 million digital studio and motion capture suite at our disposal, the future is looking very bright indeed for “Stina & the Wolf” 🙂Paul

We are currently designing a pipeline for this new phase and planning to reinvigorate our old in-house studio FOAMdigital that ran out of Portsmouth University. It will once again give students a chance to get involved in a really exciting industry project that will take their skills to the next level and help them produce some really stunning work. (As seen in our short film “Uncle Griot” & our assorted trailers and teasers.)It’s early days, but we shall be posting more details, examples and deep-dives as we progress, and with the addition of the University’s amazing new £7 million digital studio and motion capture suite at our disposal, the future is looking very bright indeed for “Stina & the Wolf” 🙂Paul