Building Dravazzeki

Releasing our short film, and what’s next for our feature?

The Drama Cut

“Griot is dumped in the animal shelter”

“Griot is dumped in the animal shelter” “A moment of calm with Griot in the forest”

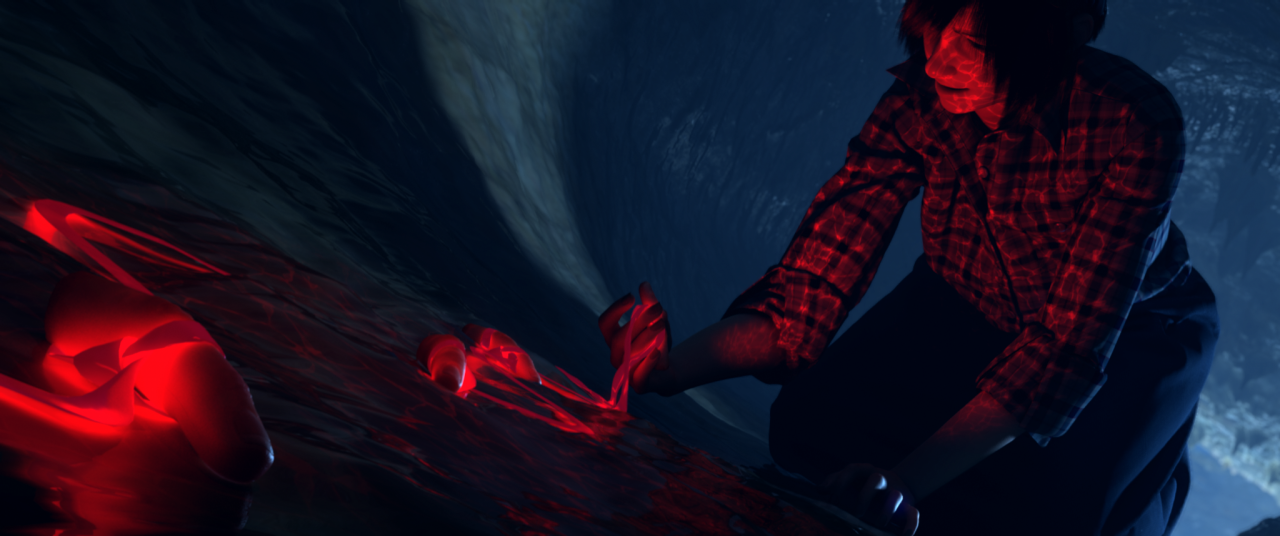

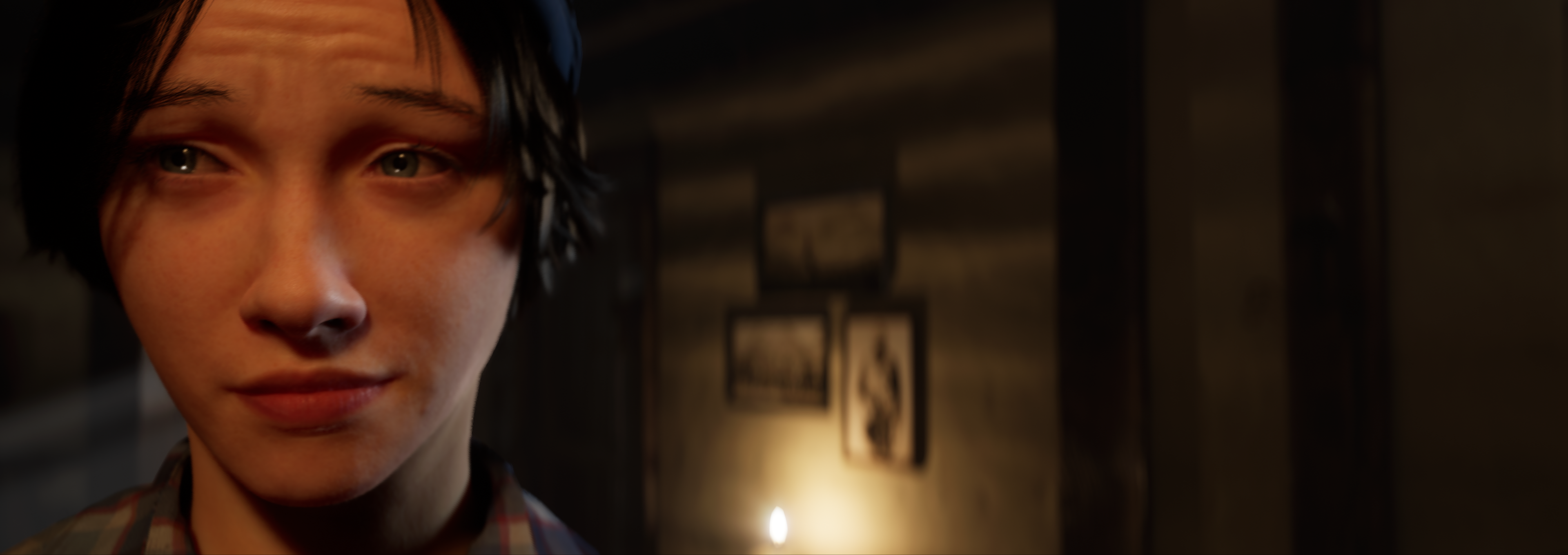

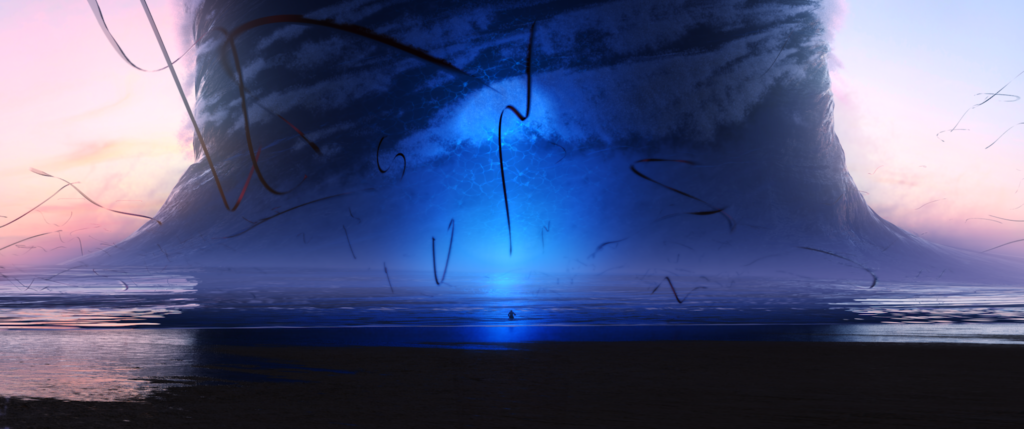

“A moment of calm with Griot in the forest” “Stina follows a horrifying trail into the underworld”

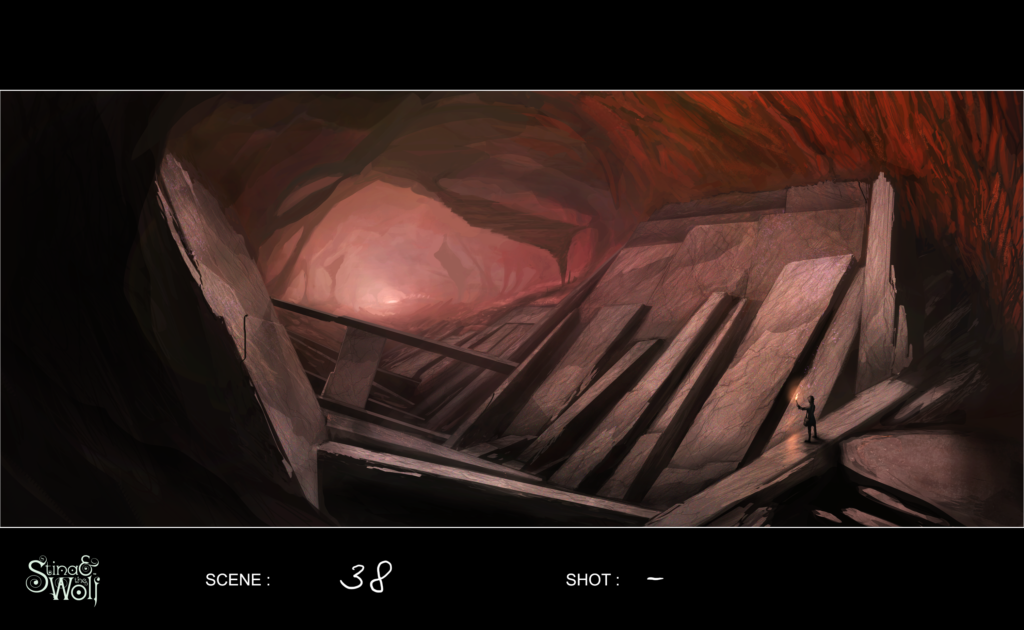

“Stina follows a horrifying trail into the underworld” “..The trail leads down into the dark depths”

“..The trail leads down into the dark depths”What’s Next?

“Stina and the Wolf” – the Mini Series

Finishing the sequence in UNREAL

It’s been a while since my last post, mainly because all my spare time has been going into finishing our sequence. (There are never enough hours in the day!) But now seems like a good time to reflect on how far we’ve come and what we’ve been up to.

We’ve been working hard on our sequence using the UNREAL game engine, which has been both rewarding as well as challenging. The sequence is a whole scene taken from our full 2 hour drama cut of the movie developed from the orginal motion capture sessions. It occurs early on in the film, as we are getting to know the characters and the world. We chose it as our first test scene in UNREAL because it provided a good range of challenges for our pipeline and our conversion from the late, great Softimage to the UNREAL system. The scene contains multiple talking characters that require close-ups, and it has a fully keyframe-animated character – Griot, who has a lot of fur, amogst other challenges. It has also lets us experiment with a form of set construction called “kit-bashing” where you take elements from the extensive UNREAL model library and combine them to make full sets, (In addition to modelling and texturing bespoke assets as needed.) This has proved a challenge, as the majority of UNREAL assets from the Quixel Megascan library are scanned from real life objects. So any hand made assets have had to be modelled and textured to a similar standard of realism. This has also been useful, as it’s helped us get our modelling, texturing and shader making skills up to the correct standard using Maya for modelling, Substance Painter for texture creation, and UNREAL’S internal shader node system to build the shader networks.

Shot Production

We are now firmly into Shot Production, having built enough of our assets (models, landscapes, rigs and textures) to get us started. Shot Production is the stage of the process where focus falls on the needs of individual shots, rather than the broader aspects of design and asset construction.

What is slightly different in UNREAL compared to a traditional film pipeline is the ability to see the final look early on and integrate that into earlier stages. For traditional VFX and animation films the process is usually very linear:

Our clothes are being designed and simulated in Clo3d & Marvelous Designer. Some of our talented students Isaac Macheri and Mya Mistry have built the costume, with the simulations currently being run so we can export them into the UNREAL scene. (For nerds: We are using the alembic data format; this allows us to add frame-by-frame geometry animation of pretty much anything we want and although very heavy on storage seems to be working well so far.)

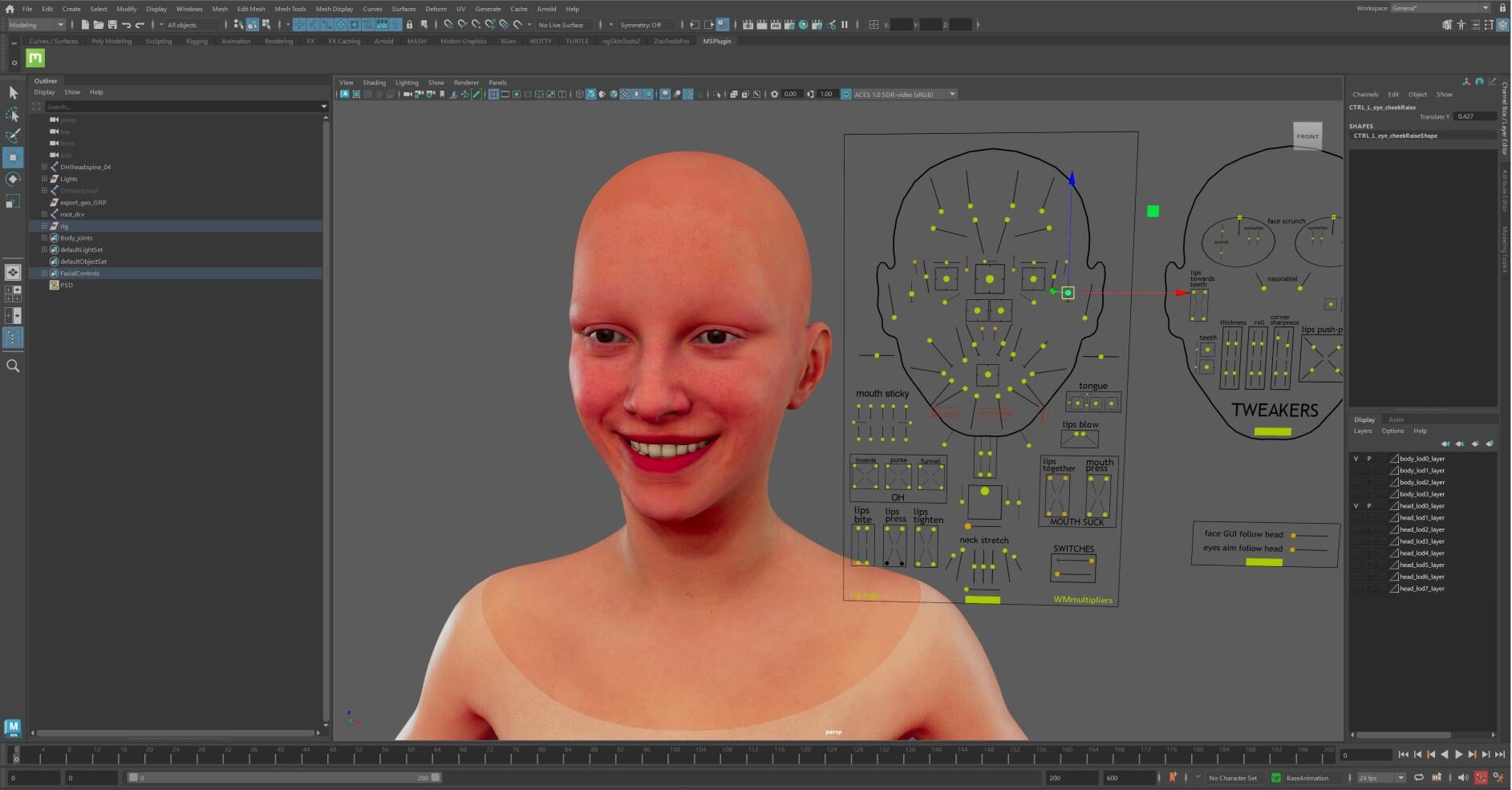

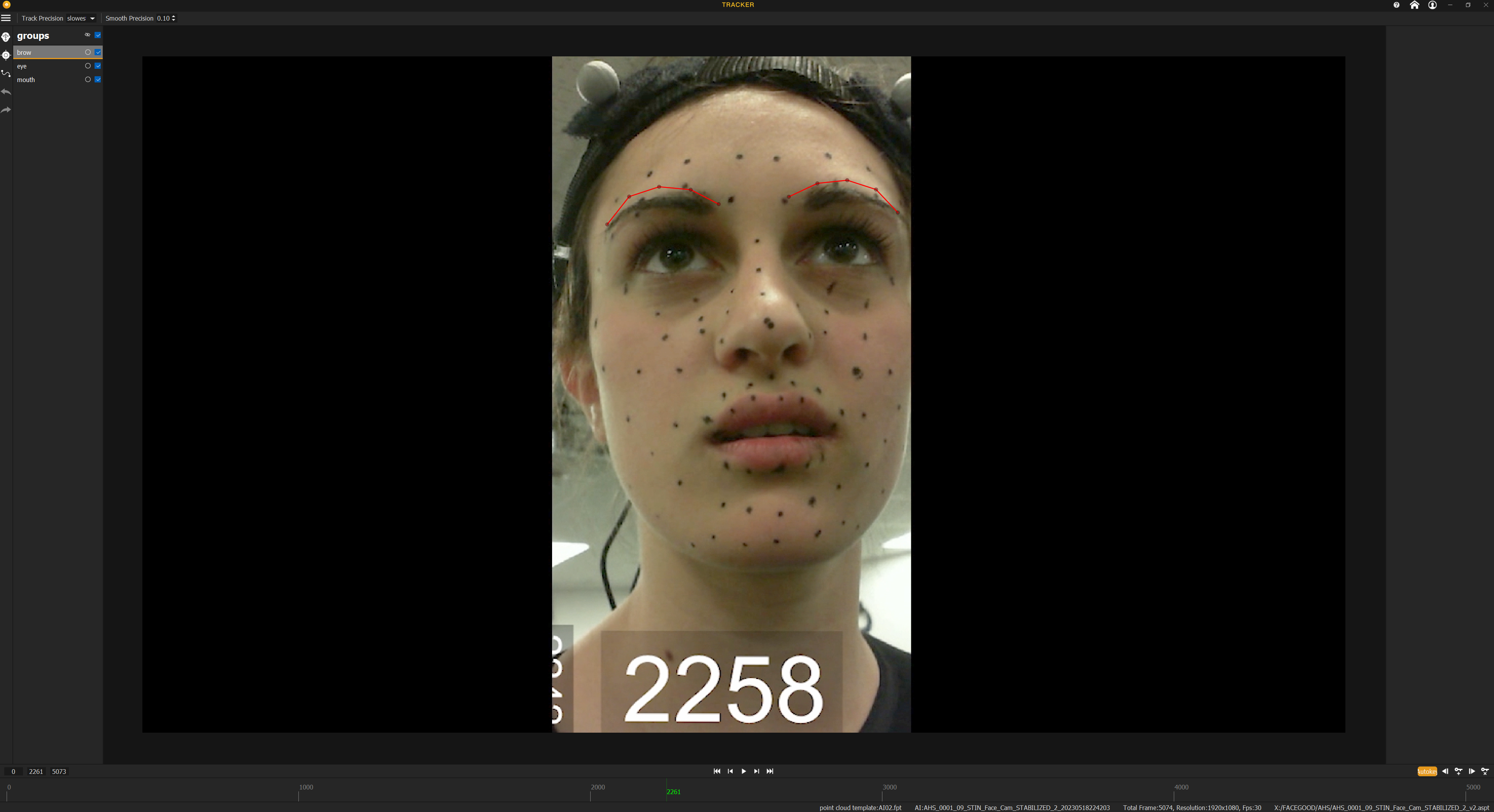

We are also now finalising our facial animation pipeline and are using FACEGOOD to help us translate our actors facial performances onto the facial rigs from our Metahuman characters:

Stage #1 – Facegood Retargeter

Stage #1 – Facegood Retargeter

Stage #2 – Retargetting onto the Metahuman Face controls in Maya

Stage #3 – Importing into UNREAL

We are currently tackling the finger animation (This is done with hand-keying, as it’s was not captured with our orginal motion capture) and refining our assorted post effects and render settings to get the best render quality we can. We have just taken delivery of a fancy new machine for the project (With a GTX4090 graphics card for the nerds out there!) so are hoping this will really help speed things up and allow us to ramp up the settings to get the best fidelity we can.

That’s all for now folks, more soon…

Stina & the Wolf : A fairy tale of dance and music, coming soon…

A taste of what’s to come:

~ Stina & the Wolf ~

(a musical fairy tale)

1 – The Village

Stina is an ordinary girl, and she’s an orphan, of course. She lives in a small village high in the mountains with her unforgiving aunt and a nice, but goat-bodied uncle. The village is a hard place: brutal tradition, endless ceremony and always a cup to wash or homework to do. Today she is doing her chores, like every other day. As she toils away she looks towards the distant snowy mountains. She watches an eagle as it soars above a distant peak, then vanishes into a cloud; she follows it into a daydream of a better life, as a woman.

“Stop daydreaming!”.

2 – The Snow

The next morning she wakes to a glorious sun. Her aunt is asleep. Her uncle is in his basket. She creeps past them unseen into the wild meadows. She has escaped, for now. It suddenly begins to snow. She has never seen snow before. It’s new and exhilarating. She likes the feel of it as it settles on her skin. She runs into the blizzard and is soon lost, although she doesn’t know it yet.

3 – The Caravan

Finding her way back to the village, she follows a strange caravan of brightly coloured wagons led by a charming devil. He is flanked by wild dancers wearing the beasts of the forest.

4 – The Baiting

The caravan sets up in the village square and erects a high-walled arena offering a test to boys on the threshold of manhood. It soon draws a crowd of excited teenagers. Only boys enter. Once inside they begin enthusiastically killing wolves but are tricked into the awaiting cages. The caravan leaves with the boys inside.

5 – Transformation

Stina follows it down into the forests below.

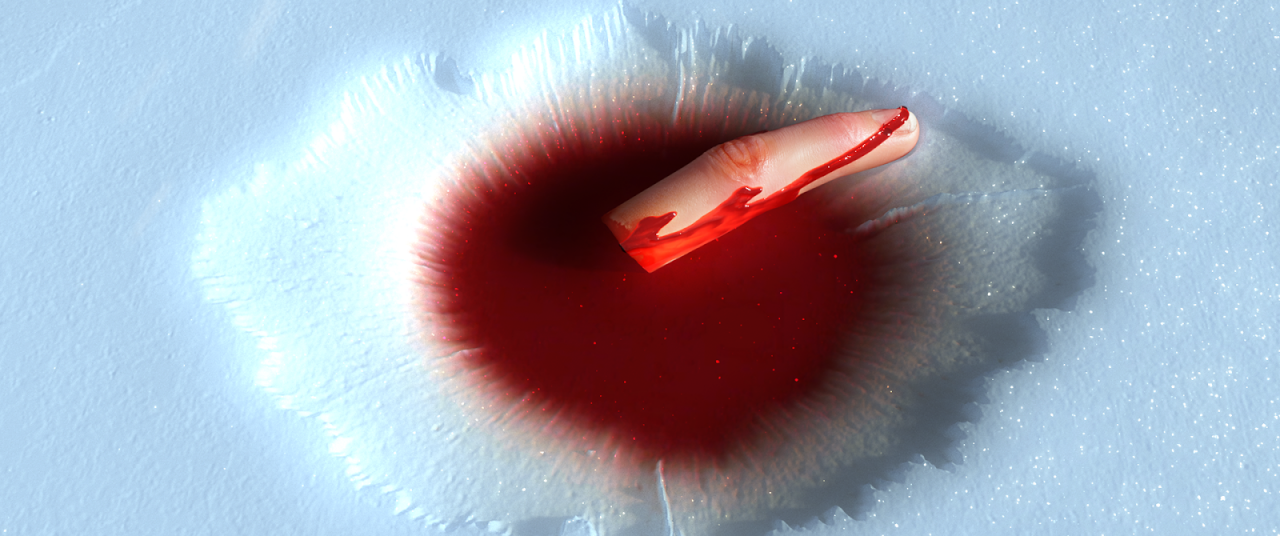

Losing the trail, she stops to rest by an icy lake. Lost, tired and alone, she regrets ever leaving the comfort and safety of the village. Washing cups isn’t so bad, not really. Suddenly the moon appears. She fails to notice it turning blood red. She catches her reflection in the ice. Her eyes are a poisonous yellow. On the far side of the lake a creature howls. She is surrounded by a pack of hungry wolves. The blood light engulfs her and she becomes a wolf. She is hungry and joyful. She dives into the forest to feed with the pack. She follows as they tear through the trees, finally diving into the ground, sated, to rest under a giant oak.

5 – The Underworld

When she awakes she is deep underground and only a girl. She makes her way down into the earth and enters the underworld, arriving at a giant ocean. A lone wolf stands guard on a rock and calls to her, saying no girls may enter. She persuades him she’s a boy and he lets her pass (easy). He summons up the horde from beneath the waves. All the real and fantastical creatures of the forest emerge and process down into the depths. They carry her down to the lair of the charming devil and she arrives through a giant wall of water.

The lair is dark and empty. Suddenly the devil emerges. He is sarcastic and rebukes her for her boyishness. But Stina isn’t afraid. Boys are boys. She replies softly and they dance. He resists at first, but she soon teaches him to dance like her, and they move in harmony. Softened by the dance, he doesn’t notice as she releases the boys and they flee into the wall of water, leaving the charming devil pirouetting off into the darkness. The horde carries them all back to the surface, travelling through every terrifying level of the underworld. Finally they burst into the brilliant mountain sunlight, right next to the village.

6 – Home

The village is full of snow and the villagers are gone. In their place are wolves. They are eating viscera and staining the white snow red. With her new found skills, Stina casts a spell and returns the villagers to human form and the boys reunite with their families (they also put their clothes back on!). She calls out to them, but her voice is now that of a wolf, and they throw stones. She watches from the trees as the villagers go about their lives; her aunt does her chores, her uncle eats the grass. She knows she can never go back. She is a wolf and she is a human. She turns from the village and runs into the mountains to live with the other beasts of the forest forever, the real ones and the fantastical ones.

~THE END ~

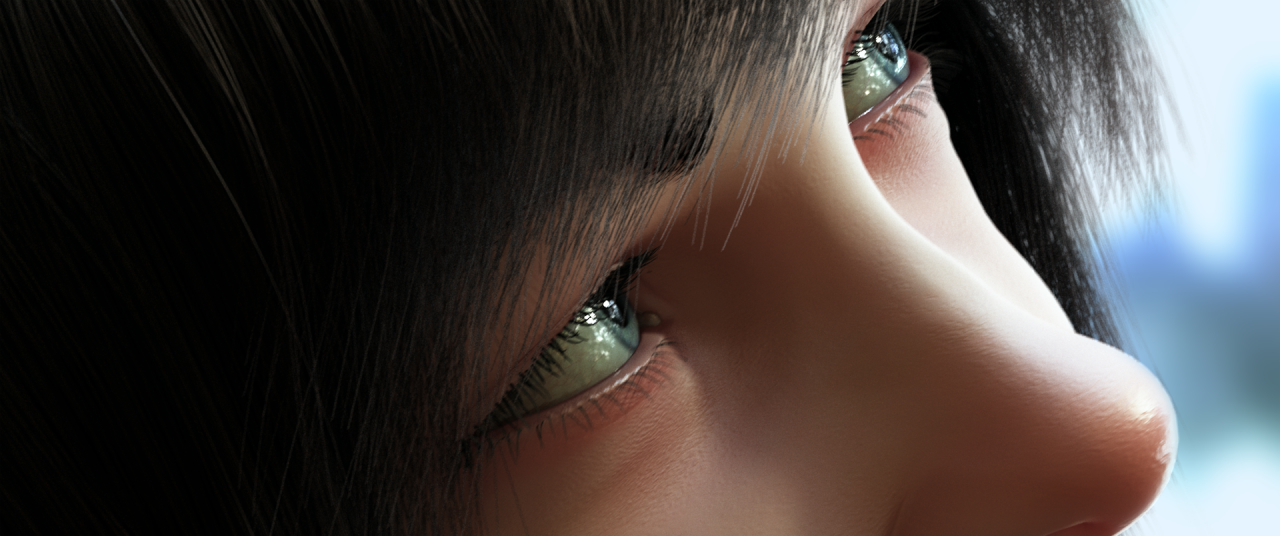

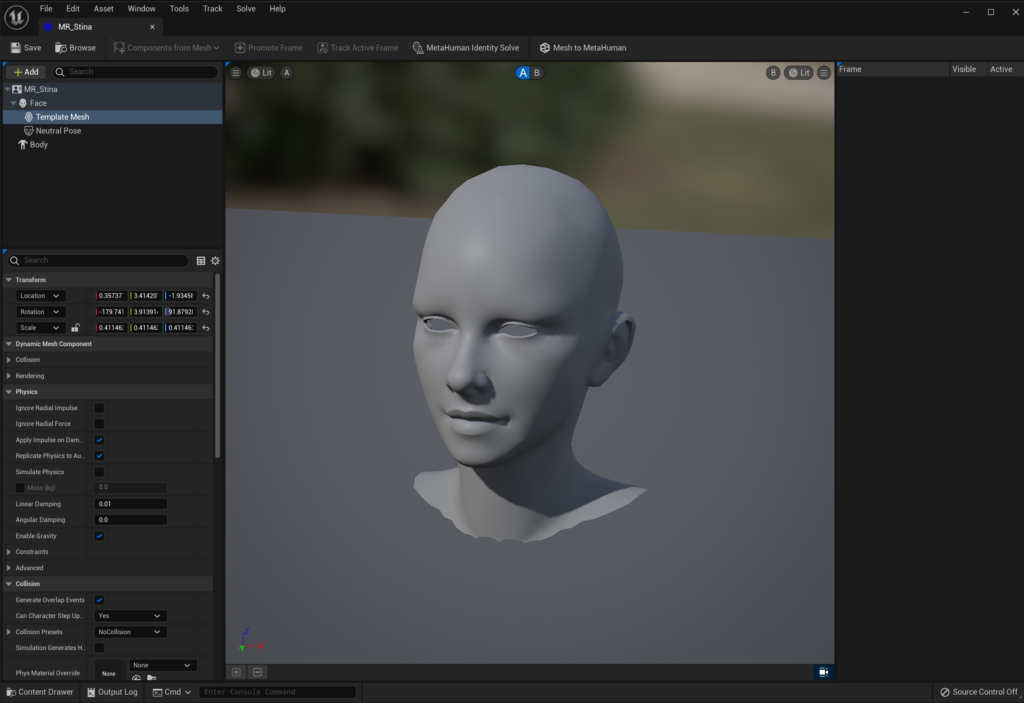

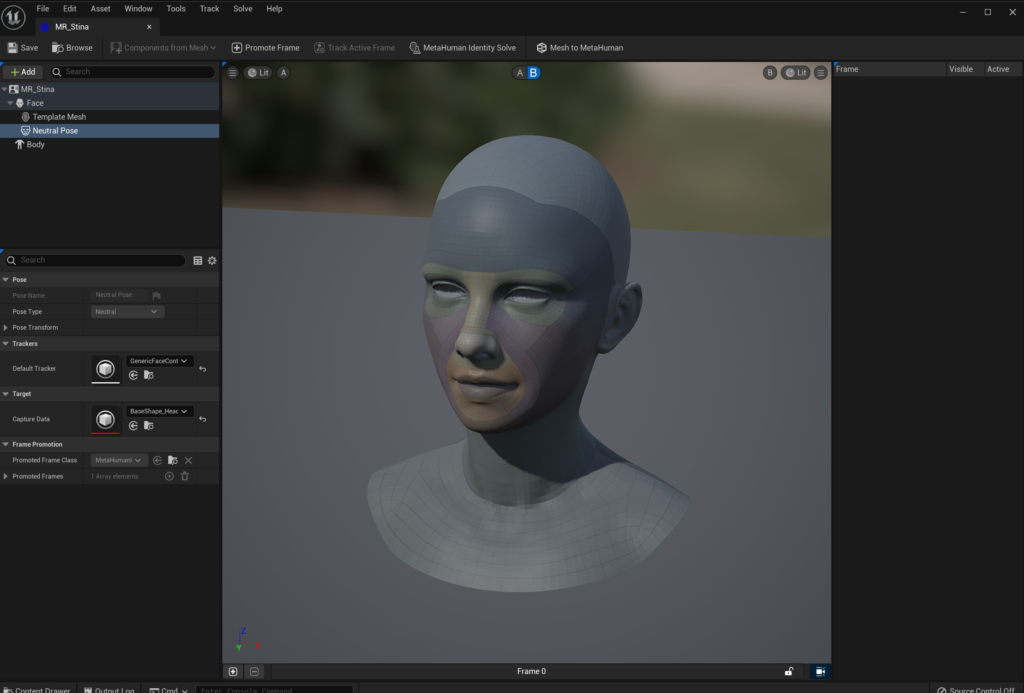

Stina becomes Metahuman

A quick post about the transfer of Stina into her new world as a Metahuman in UNREAL 5

The Stina model has existed in Softimage with our custom built facial animation system for some time. It has been the cornerstone of our production, so we were super excited to see how it faired in Metahuman, the new ground breaking character system in UNREAL. A recent development in the software now allows you to load in your own custom meshes and fit the system to it. (Before you had to make new heads out of blending presets.)

First we exported the base head sculpt out of Softimage in its relaxed position:

Then converted it into a Metahuman template that identified the different regions of the face to add the animation and texturing system within unreal.

Then added in the texture, hair and animation system by tweaking a wide range of built in presets. All surprisingly straightforward.

And a range of motion test:

The results are astonishing, verging on photoreal. It’s very strange to see the sculpt we’ve been using for so many years almost seeming to take on a life of its own! The next stage is to see how it responds to Becky’s performance. Really looking forward to bringing the other characters to life now. The Meta-world awaits!

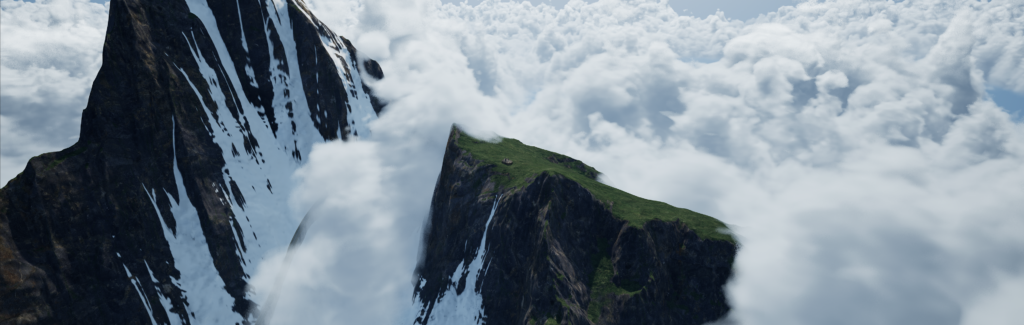

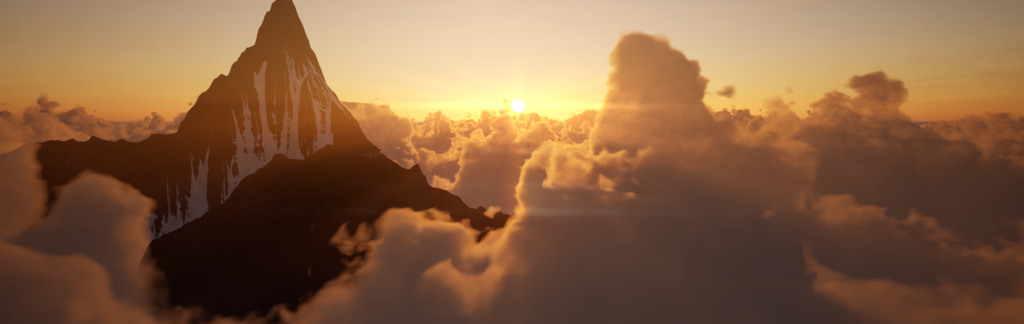

Location scouting the UNREAL

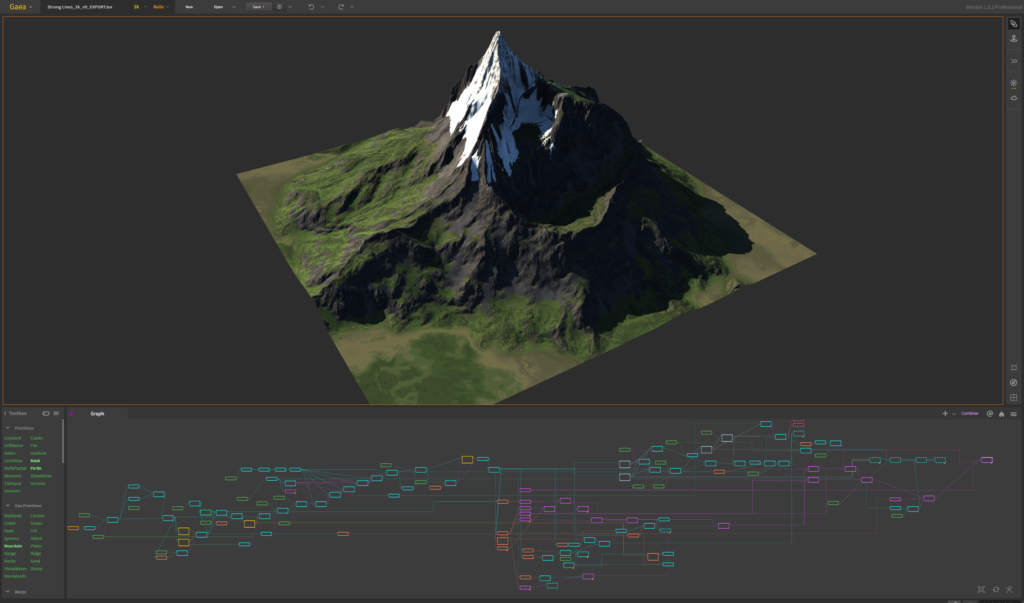

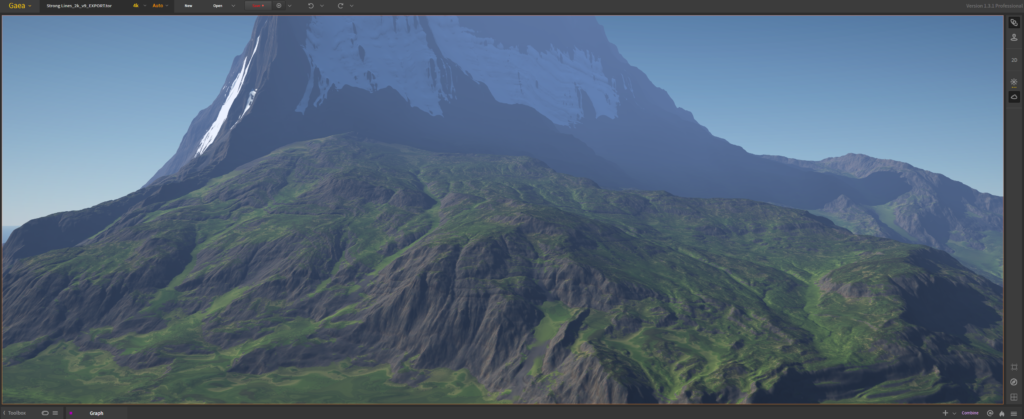

The world map is being built with GAEA, a fantastic node-based tool for making landscapes from geological principles: Layering stratification, erosion and sedimentary flow.

This map is then used to deform the terrain in UNREAL, where we use the different maps exported from GAEA (height maps, erosion maps, sedimentary flow maps etc.) to help position the smaller, high-frequency textural details UNREAL can help us create, like grass and rock (Utilizing the fantastic BRUSHIFY shader packs as a starting point.)

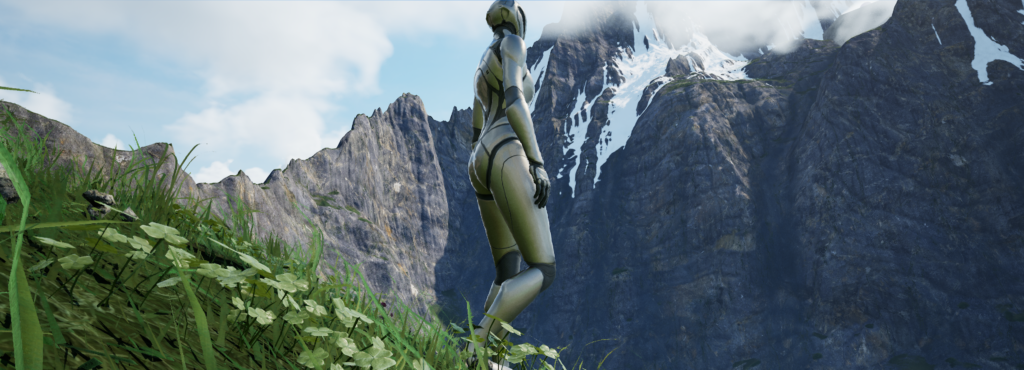

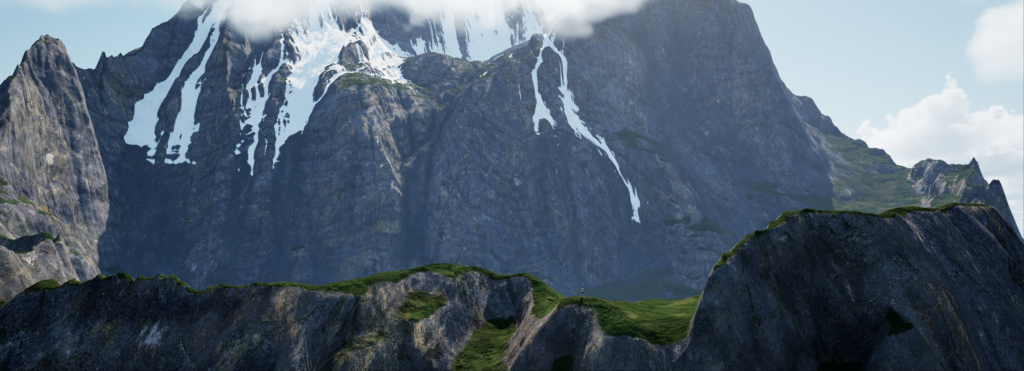

It’s an amazing new experience, to be able to make a CGI environment and then run around it location scouting. (Below with UNREALs built in avatar. No Stina hasn’t become a cyborg!) A very different paradigm to the purely design-based approach of CGI we were previously used to. We can now run around and discover things about the world we didn’t know where there, reacting to it in real time like a photographer exploring an unfamiliar landscape; experiencing different compositions of light and form. The ability to instantly change the time of day with Ultra Dynamic Skies makes this even more exiting; how will the vista look at midday? Will the setting sun totally transform the mood?

Standing high up a on mountain pass looking down through a cloud as it diffuses the sunlight over the village:

Looking up at our peaks from down in the valleys:

Looking down on Stina’s aunts house from high above the cloud layer:

Stina’s field and the aunt’s house at sunset:

We are also beginning to design our other pipelines, from animation and facial motion capture through to cloth and fluid simulation. A lot of work ahead, but we’re already assembling a great team and have achieved a lot more than we ever expected in just 2 weeks. (Back at the start of the project this level of fidelity would have taken forever. Technology has come a long way in 10 years!)

We’ll be posting some videos soon exploring our new world in more depth, so keep your eyes peeled…

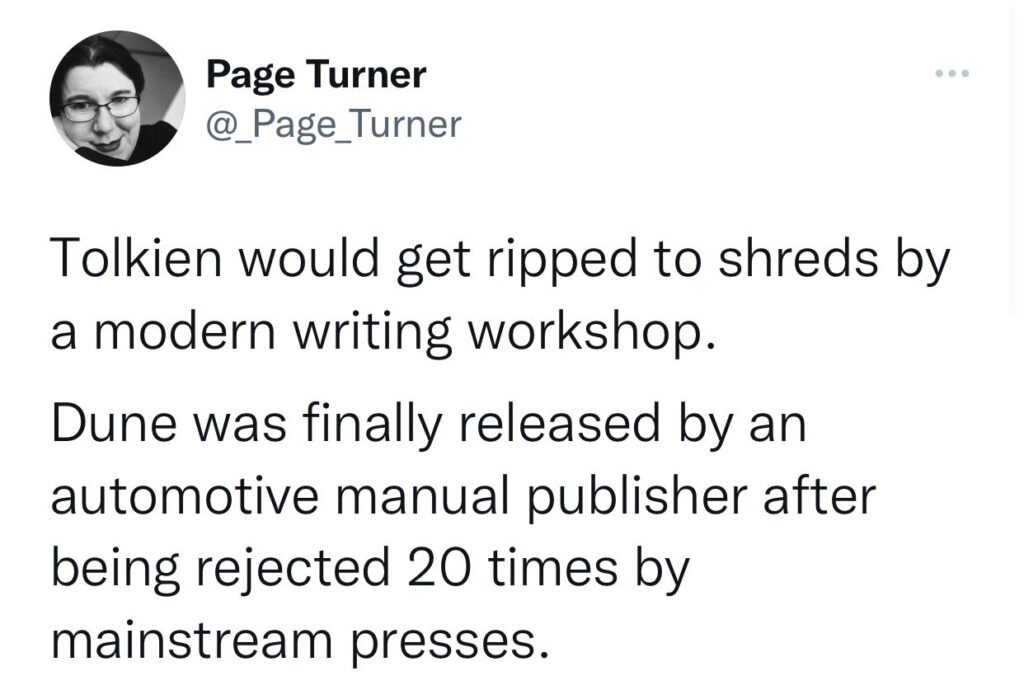

Falling down the Hollywood screenwriting rabbit hole

As a follow on from my previous blog about the exciting future of the Stina project, I thought I’d write a bit about the Hollywood screenwriting rabbit hole I fell down that prompted not only endless rewrites after we’d shot the film, but almost managed to mangle the original idea.

I’m not alone in this; it’s a very modern phenomenon. We live in a time where virtually every specialist area you can think of has a head-spinning amount of youtube and other online tuition and master classes to immerse yourself in. In my case it was the craft of screenwriting, which is very much a learned craft. Having a “great idea for a movie!” is one of the smallest aspects of what finally translates into a good screenplay and ultimately a good film. A very simple and derivative idea can make an amazing film if structured well with great dialogue and characters, and a great idea can make a dreadful film if the former falls flat. This is great advice. The problem is there is an almost infinite wealth of “great advice” out there on screenwriting, and not all of it will fit every type of film project. In fact, as I eventually realised, the majority of advice out there relates to a very specific type of film: A Hollywood hit.

In the case of the Stina script, (and in the case of most screenplays worth anything.) the magic happens in the rewrites. I’ve been studying screenwriting and writing screenplays for quiet a few years now, and my drafts for this script were well into double figures. The excellent writer/director Thomas Paul Anderson captures the process:

“Screenwriting is like ironing. You move forward a little bit and go back and smooth things out.”

The first draft is a blueprint, hopefully an inspiring one, full of loads of ideas and a solid basic structure, (depending on how detailed your outlining was) but with lots left to discover about the characters and their journeys. Often characters will get themselves to a point in the writing where they need to take a different direction to the one you had mapped out for them; it’s a cliche, but they do often take on a life of their own and move in unexpected ways you have to follow, and this often has knock-on effects in other parts of script that need constant revision if you want stay true to the character’s journey. (I found this a lot in a more recent project: “DEAD HEAD WOOD”, even whilst doing the pre-viz, where I ended up constantly feeding back scene-by-scene into the script.)

“The truth is it’s not the idea. It’s never the idea. It’s always what you do with it.” – Neil Gaiman

It’s from this position on the Stina project that I found myself rewriting dialogue and often whole scenes, even after our first rehearsals, always chasing “perfection”. The trick here is knowing when to stop; this should be when the film is working and carry’s your themes as effectively as it can. That’s not as easy as it sounds, as you can often get too close to a project and perspective can be hard to find. Of course, an end point should definitely come after you finally shoot it; that’s it, that’s the end. It is what it is, now the editing takes over. But that is when I fell down the rabbit hole.

Hollywood films serve a function. They are a specific product, for a specific audience and generally require a specific formula. Many are clearly excellent films, but it’s a mistake to think they encompass all good filmmaking has to offer. (Cannes Film Festival anyone?) This is especially relevant if you’re attempting to explore ideas and forms that don’t necessarily embrace the mainstream and the biggest potential audiences. (Not to mention the direction funding inevitably squeezes a writer in. Being a writer and a producer aren’t always happy bedfellows!) In our case, the first cut I had of the film, made from footage of the Mocap shoot and storyboards had really captured the atmosphere, characters and themes of the original idea, but sacrificed some of the structural tidiness and accessibility of a Hollywood movie. This was reflected in early feedback I had from some professional screenwriters. The problem I then encountered was one inherent to all feedback: What do you do with it? It was really useful feedback, but how do you use it to improve your work constructively? For example, how would some of my favourite authors have reacted to the sensibilities of a modern writing workshop? The author Page Turner: In my case I started voraciously consuming any and all industry advice videos, taking courses and seeking tips everywhere I could about how I could rewrite the “perfect” screenplay; with a plan to reshoot it one day, in a mythical future when I could make it all as a multi-million dollar live action feature. (And i’m really not getting any younger!) The problem with this is that I never looked at the small print: the places I was looking held the keys to the Hollywood “correct” process; how to make an entirely enjoyable and entirely tidy film that will work for the most number people built on foundations of proven storytelling methods. Sounds great doesn’t it? But were all of my favourite films really “enjoyable” in the traditional Hollywood sense? And would they fit neatly, or at all into the structural templates used by Hollywood screenwriters? (Good luck fitting “Mulholland Drive” into the cookie cutter) “Stina & the Wolf” was now being unwittingly reshaped into a movie format that could never express the strangeness, otherness and ambiguities of my original Idea.

In my case I started voraciously consuming any and all industry advice videos, taking courses and seeking tips everywhere I could about how I could rewrite the “perfect” screenplay; with a plan to reshoot it one day, in a mythical future when I could make it all as a multi-million dollar live action feature. (And i’m really not getting any younger!) The problem with this is that I never looked at the small print: the places I was looking held the keys to the Hollywood “correct” process; how to make an entirely enjoyable and entirely tidy film that will work for the most number people built on foundations of proven storytelling methods. Sounds great doesn’t it? But were all of my favourite films really “enjoyable” in the traditional Hollywood sense? And would they fit neatly, or at all into the structural templates used by Hollywood screenwriters? (Good luck fitting “Mulholland Drive” into the cookie cutter) “Stina & the Wolf” was now being unwittingly reshaped into a movie format that could never express the strangeness, otherness and ambiguities of my original Idea.

In the end it’s a confidence thing. I had a strong idea of theme, story and character and the first cut was pretty close in most areas, it just needed a few extra scenes and a few tweaks, but the feedback had knocked me sideways, and instead of just applying the fixes it needed and moving on, down the rabbit hole I went. I became increasingly obsessed with completing every character’s arc neatly, structuring every beat to hit the Hollywood defined structure and comparing my film to others that were regarded as perfect examples of the craft; all great films, but all bearing absolutely no relationship to my original vision.

What I finally ended up with was a dense story overcrowded with detail and ideas. It tried to complete every character arc, tidy up every loose end, destroy every ambiguity, justify every aspect of every character’s motivation, and left no space for the other-worldly inexplicable melancholy of the original; it wasn’t dreamlike, it had no yearning for meaning beyond what was seen and squeezed out most of what I loved about the early cut. But by that point my confidence was shot. And in tandem with it becoming increasingly clear that the technology we needed was still no where near affordable enough, I all but abandoned the project.

But it was saved; partly by what I touched on in my last post: Current technology finally getting to the place where it is entirely possible to complete a film like this. But you need more than that to drive you to make a film. It’s often a seemingly impossibly difficult task, so you have to really want to make it. It has to be special.

I decided, a few months ago to watch the last cut I had made before the endless rewrites, just me and my partner. I’d done it so long ago I figured it would be like watching someone else’s film. It was a cut I dimly remembered getting very emotional about at the time. I knew I had already added the few additions it needed to make it work, before disappearing down the rewriting rabbit hole never to return.

On rewatching it, it brought me close to tears, it just felt right, it didn’t need all the other bumf i’d added to flesh everything out to the point of bursting. Even though it was just a bunch of kids in Mocap suits and some pencil storyboards it stayed with me for days. It didn’t hit every beat of a 3 or 5 act structure, didn’t contain every archetype of Joseph Campbell’s “the hero’s journey” and left some characters almost entirely arc free, but it made me want to cry. It was truthful; not just to my original vision, but to the characters, and to life. That’s all it ever needed.

So now we’re all very excited, as not only do we have a story (we always did) and performances that express the original vision, we now have the tech to make it visually stunning, and actually finish it!

And the moral of all this, if there is one: Trust your instincts. Feedback used wisely is invaluable, but the best critic of your work is always you, you just need time, a lot of it sometimes, to see if what you really wanted to do, under all the fluff and nonsense, is actually there. Is it actually present in what you made? Is it truthful?

If it makes you cry, it’s working.

It’s clearly important to learn as many of the rules and formula of your art form as you can, especially with something as craft-dependant as screenwriting, but only to the point you are actually improving, not suffocating or entirely changing what you originally set out to express.

And as a final thought: Here’s one of my heroes: Kurt Vonnegut, on top comedy form exploring Shakespeare and Kafka completely failing to craft the “perfect” story:

Stina & the Wolf’s journey into the UNREAL

So, we have some very exciting news on the “Stina & the Wolf” film.

In previous posts I had discussed making it as a live action feature; starting again, completely from scratch. This always stung, as there were so many great moments and performances from our original shoot that would be lost and need recapturing. At the time we just couldn’t work out a way to finance it, to get the huge budget you need to pull off an entirely motion captured film to the quality we wanted.

In previous posts I had discussed making it as a live action feature; starting again, completely from scratch. This always stung, as there were so many great moments and performances from our original shoot that would be lost and need recapturing. At the time we just couldn’t work out a way to finance it, to get the huge budget you need to pull off an entirely motion captured film to the quality we wanted.

The technology was only affordable to huge studios with hundreds or even thousands of VFX artists working at the top of their game. There were just too many sets, too many performances that needed complex facial character models and animation systems, too much varied and detailed natural scenery; too many complex cloud and outdoor lighting scenarios; all of it teased by our concept art:

Then 12 years passed by (Yep, it really was that long! This all kicked off back in 2010) and technology finally caught up.In the last few years facial animation technology has been massively democratised, as has access to amazing scanned models and real-time realistic lighting and cloud technology. This is best represented in the incredible new game engine UNREAL 5:

Then 12 years passed by (Yep, it really was that long! This all kicked off back in 2010) and technology finally caught up.In the last few years facial animation technology has been massively democratised, as has access to amazing scanned models and real-time realistic lighting and cloud technology. This is best represented in the incredible new game engine UNREAL 5:

This is the way we are going with our film production.UNREAL 5 is a game changer, not just for us but possibly for the whole industry. Now these examples above are still produced by extremely skilled industry level artists. There is no magic button here, there never will be. (Okay, there will – AI will eventually do everything better than us, but that’s for another day.) The difference is that the majority of the assets and systems used here are free (or relatively inexpensive) and are available for everyone to use. The art comes in composing and editing them and mastering the systems. You no longer need 1000 VFX artists to make every blade of grass wobble, every facial muscle twitch, paint every plank of wood, simulate every drop of water in a cloud completely from scratch. UNREAL and their partner company Quixel Megascans have done that work for you.

It’s now entirely feasible for a small team of talented artists to produce amazing work, building on what UNREAL has already produced. It’s now, finally possible for us to make “Stina & the Wolf” as we originally intended! We are currently designing a pipeline for this new phase and planning to reinvigorate our old in-house studio FOAMdigital that ran out of Portsmouth University. It will once again give students a chance to get involved in a really exciting industry project that will take their skills to the next level and help them produce some really stunning work. (As seen in our short film “Uncle Griot” & our assorted trailers and teasers.)It’s early days, but we shall be posting more details, examples and deep-dives as we progress, and with the addition of the University’s amazing new £7 million digital studio and motion capture suite at our disposal, the future is looking very bright indeed for “Stina & the Wolf” 🙂Paul

We are currently designing a pipeline for this new phase and planning to reinvigorate our old in-house studio FOAMdigital that ran out of Portsmouth University. It will once again give students a chance to get involved in a really exciting industry project that will take their skills to the next level and help them produce some really stunning work. (As seen in our short film “Uncle Griot” & our assorted trailers and teasers.)It’s early days, but we shall be posting more details, examples and deep-dives as we progress, and with the addition of the University’s amazing new £7 million digital studio and motion capture suite at our disposal, the future is looking very bright indeed for “Stina & the Wolf” 🙂Paul